Yes, that's right. In my quest to understand British culture, I sent a fat guy who kind of looks like me to Britain's most famous landmark, Big Ben. Though the picture cuts off the top, I assure you, Big Ben towers over London like one of the shorter Manhattan buildings that nobody really even notices in the skyline. Yes, as Sondheim said, there's no place quite like London, that city that doesn't sleep until 8pm when everything pretty much shuts down except for pubs, hellish clubs and a Tesco which sells a "New Yorker" sandwich which is far, far to thin to be a New York sandwich. When you think of the UK, you don't really think of cinema. But hidden amongst the Tardises and tea are some of the greatest films ever made, enough to result in what is most assuredly my longest "Honorable Mentions" section to date, so extensive it had to be categorized by genre. So please, take a look at my picks for the Greatest British Films ever made, swing by Tom and Josh's blogs to read theirs, and don't forget to comment to share your opinion, subscribe to never miss an entry, and of course vote for out next list.

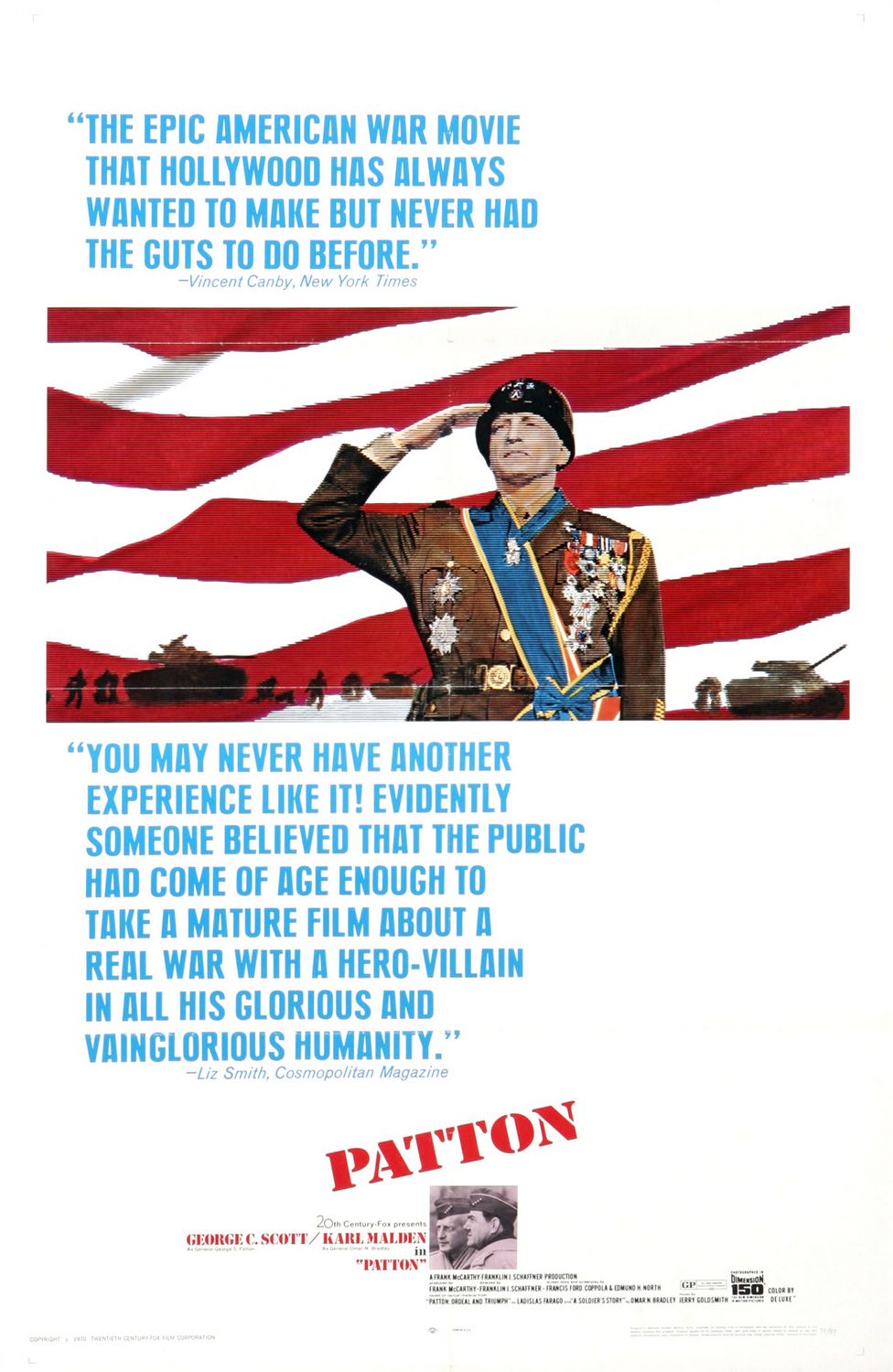

10) Goldfinger (1964)

10) Goldfinger (1964)

Goldfinger. He's the man, the man with the Midas touch. An obsession with gold so great, it will lead him to attempt an audacious robbery of Fort Knox, and only one man can stop him.

Admittedly, when we think of the Brits, action never comes to mind. Yet the quintessential movie spy hails from the Queen's country. Dr. No made the mold, and From Russia With Love proved there was potential in the Scotsman in a stylish suit, but with this third installment, the man who would be Bond truly nailed it. From the machine-gun armed Aston Martin to the bladed-hat wielding villains, to say nothing of Bond's ability to make allies with his nether regions, all of the most iconic moments of James Bond lore were established here. The film features some of Bond's greatest supporting characters, from the devilish Auric Goldfinger to the stoic Oddjob, and of course Pussy Galore (I must be dreaming). It also gives us the greatest Bond line besides his name and a drink order: When strapped to a table, with a laser beam headed for his most valuable weapon, Bond cries out "You expect me to talk, Goldfinger?", to which Auric replies "No, Mr. Bond. I expect you to die." It's no wonder when Sam Mendes went to save Bond from a pit of grit and gloom near 50 years later, he threw more than a few loving nods to this entry in the series.

Admittedly, when we think of the Brits, action never comes to mind. Yet the quintessential movie spy hails from the Queen's country. Dr. No made the mold, and From Russia With Love proved there was potential in the Scotsman in a stylish suit, but with this third installment, the man who would be Bond truly nailed it. From the machine-gun armed Aston Martin to the bladed-hat wielding villains, to say nothing of Bond's ability to make allies with his nether regions, all of the most iconic moments of James Bond lore were established here. The film features some of Bond's greatest supporting characters, from the devilish Auric Goldfinger to the stoic Oddjob, and of course Pussy Galore (I must be dreaming). It also gives us the greatest Bond line besides his name and a drink order: When strapped to a table, with a laser beam headed for his most valuable weapon, Bond cries out "You expect me to talk, Goldfinger?", to which Auric replies "No, Mr. Bond. I expect you to die." It's no wonder when Sam Mendes went to save Bond from a pit of grit and gloom near 50 years later, he threw more than a few loving nods to this entry in the series.

Best moment:

Though the MI-6 agent has many memorable moments in the film, the scene that stands out is the opening credits. Before this, the film's credit sequences were nothing to write home about. Dr. No begins with some uber-60's color dots and moves into a prototype for Mulholland Drive's opener, and while From Russia With Love had figured out hot women and projectors are fun, it's "go-go dancer" aesthetic and instrumental track (in leu of John Barry's gorgeous theme song, which was instead hidden in some random scene within the film itself). Here, in the definitive Bond credits, gold-tinted women, barely dressed, become movie screens, playing out an overture of the adventure to come, while Shirley Bassey belts out the classic theme tune. Every Bond credits since has tried to match its intensity and sexuality, but none have captured the essence of what makes Bond Bond quite like this. It's elegant and dangerous, just what sets the spy apart from all the other action heroes. Plus, this credits sequence had its own exhibit at the MoMA. Who am I to argue against that?

9) The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

David Lean's take on Pierre Boulle'sWorld War II-set novel (itself based on the construction of the Burma Railway) was released to massive acclaim upon its release, praised for it's stunning visuals, brilliant performances, and brilliantly bold examination of the human spirit. Yet, unlike a lot of films "for their time", Kwai holds up remarkably well, and manages to skewer the British spirit most WWII set films tend to celebrate. It his sense of national pride, and his twisted idea of defying the enemy, which forces Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson (played with brilliant conviction by the legendary Alec Guinness) to demand his men construct the finest bridge they can for their enemy, who is holding them captive in a prison camp. Lean creates a gripping war story, with one of the most memorable whistles in film history, while tackling the old-guard idea of "Honor above all", shining a mirror on it's foolish implications in this new modern world. The film stands as a precursor to the rebellion of the 60's, ridiculing authority figures and ancient ideas of nobility and pride, one of the first to use World War 2 not to evoke patriotism, but to create a discussion of what this new, more connected, more destructive world is, and it's visions of jungle warfare were troublingly prescient for the coming years.

Best moment:

**SPOILERS**

For nearly half the film, the posh and pompous Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson demanded his rights from his captors, for the other half he demands pride in workmanship of his own men, forced to build a bridge for the enemy. Beyond his knowledge, a conspiracy is crafted to destroy the bridge, which upon discovery, Nicholson sets out to diffuse. Only when he witnesses the type of carnage he has long not seen does he remember what war is, and realize the terrible thing he's done in the name of British honor. The chaos that ensues exposes the horror, confusion and, yes, "madness" of war in a sequence so bleak and hopeless it makes Apocalypse Now's climax seem a comedy.

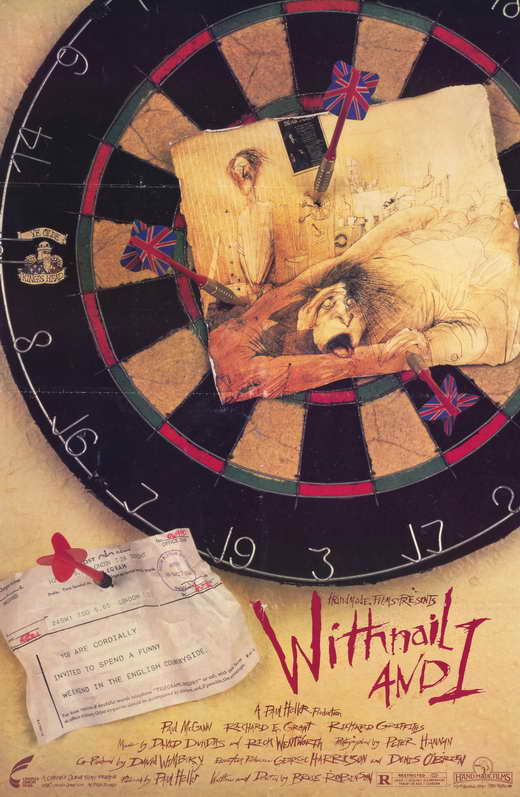

8) Withnail & I (1987)

8) Withnail & I (1987)

My American readers will likely never have heard of this Bruce Robinson directed, George Harrison produced 80's comedy, but it should be noted that over in it's nation of origin the film holds a cult comedy prestige on par with Animal House, with some students even having posters of the perpetually drunk Withnail on their walls. Set in the late 60's, two joint smoking, pill popping unemployed actors (played by Richard E. Grant and the Doctor with the shorter tenure, Paul McGann) decide to take a relaxing holiday in the counter, complete with molesting uncle, unkillable poultry, and terrifying pub-cruising men who may or may not "fuck arses", the film is full of razor-sharp wit and brilliant slapstick. The interplay between Grant's Withnail and McGann's unnamed narrator is so quick and the humor so broad that the film is instantly relatable, even for those who've never dreamed of taking "a nice little holiday in the country".

Best moment:

"I think you should strangle it instantly, in case it starts trying to make friends with us." Upon seeing that their dinner delivery is, in fact, a live chicken, these two bumbling thespians attempt to prepare the bird, giving Withnail the opportunity to say this author's favorite line of this infinitely quotable film, "How do we make it die?"

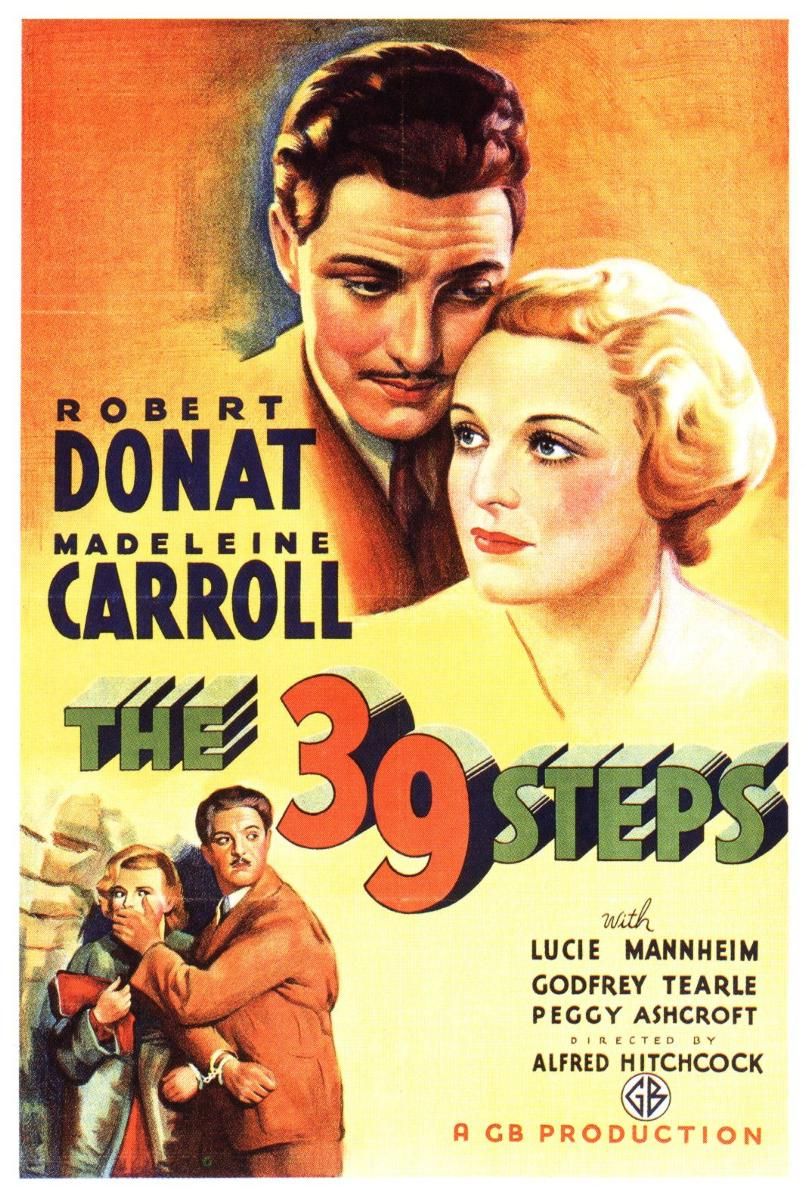

7) The 39 Steps (1935)

7) The 39 Steps (1935)

One would have to be mad to make a list of "Best British Films" and not include something from Hitchcock, a man so widely esteemed in the community he's practically The Beatles of cinema. However, one must remember his more terrifying (Psycho, Vertigo, The Birds) films were made here in the USA. While in the UK, Hitchcock was known for thrillers. Black and white tales of espionage, filled with twists and turns, mystery and suspense, and always an air of romance between its dashing lead and femme fatale. The high water mark of his home turf thrillers is undoubtedly the dashing adventure The 39 Steps, based on the classic John Bunchan tale. This film has every element of a Hitchcock classic, and it does them to the finest effect. The film is also uniquely British, substituting what would have been the standard for American noir (brute force and a hair of gunfire) for a great deal of clever planning and verbal slight-of-hand. Hitchcock used to be much better at subtle sexuality than a train going into a tunnel, and it shows in the brilliant scene at the inn where our unwitting hero Hannay (Robert Donat) is handcuffed to the alluring Pamela (Madeleine Carroll). The film is the kind of adventure story young boys used to thrive off of and play out in their yards with sticks and sheets. Of course, that type of ripping yarn has been lost to Call of Duty and overly-worried parents fearing movies can warp a child's mind rather than expand it. Yet, with a film as perfect at The 39 Steps, for a few moments you can take a step back and bask in the magic of thrills without horror, heroism with a sense of whimsy, and the kind of cultured cleverness the Brits long imbued through their stories.

Best moment:

Our hero, who took a woman home who claimed she was a spy, has just seen her murdered. He has to flee the scene, but spies two men out front who very likely want to silence him before he has a chance to pass along whatever info his companion may have relayed. In a stroke of luck, a milkman arrives. Yes, we've seen scenes like this a thousand times, and in the typical American noir, Bogart would knock the man out cold with a pistol, tie him up and take his clothes for a quick getaway, only to be exposed at the last second and have to shoot his way out. Hitchcock, however, takes this set-up and plays it out far more realistically, and in a fashion that can't be described any other way than so, so god damned English.

6) Trainspotting (1996)

6) Trainspotting (1996)

Forget Requiem for a Dream. The most gripping, honest and real portrait of heroin addiction also happens to be funny, fast paced and has one of the best soundtracks in recent memory. Danny Boyle's sophomore flick examines the junkies of Endinburgh in the late 80's, and takes its story from Scott-lit icon Irvine Welsh's book of the same name. Yet, while Trainspotting shows the horrors of heroin addiction, from Renton's "minor" indiscretion and fecal-matter diving to the death, OD's and nightmarish fits of DT-ing, the film is at its core more than that. Like the Scotch On The Road, its the story of one man's quest to rise above the misery of his lay-about peers thats often misinterpreted to be about the fun of being a layabout junky. With this film, Boyle unleashes a flurry of iconic moments and daring visuals unmatched by any other film in his career, and a career-best performance from Ewan McGregor brought this film so much acclaim as to be ranked the 10th greatest British film of all time by the BFI, stating once and for all that the UK is the land of hope, glory and heroin "better than any cock in the world".

Best moment:

I've talked already at length about the marvelous opening scene, declaring it the 7th Greatest Opening Scene in all of cinema, so for this article I've chosen a different scene. Renton returns to the needle, but goes too far, OD-ing in a manner both disturbing and beautiful through Danny Boyle's fabulously shot sinking effect, satin rising up around Renton's vision as he's being hauled into a cab and dropped on the hospital's front step. The sequence has forever been inextricably linked to late Lou Reed's classic "Perfect Day" off of the stellar Transformer (a song rumored to be about heroin use), enough that seeing it in a Playstation ad or sung by Susan Boyle just feels wrong now.

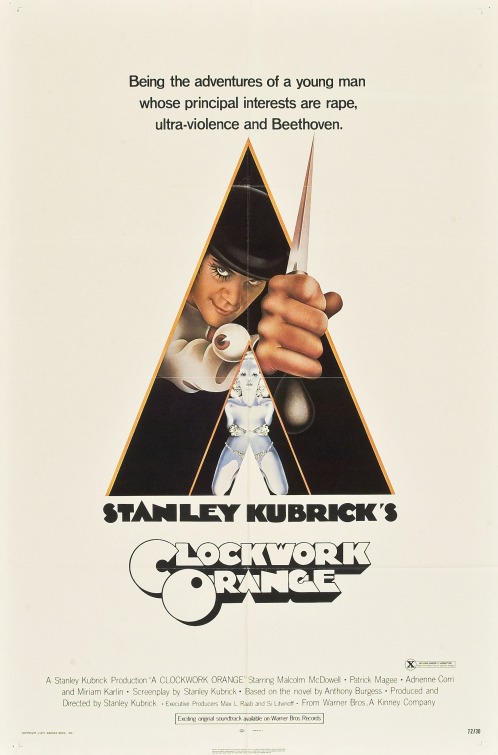

5) A Clockwork Orange (1971)

5) A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Even the most amateur of film fans would be outraged to see a list of British films that ignores the two well-known English directors, Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick. And though, like, Hitchcock, most of Kubrick's best-known films were made in the USA (or at least US co-productions), there was one film in his career so dark and disturbing, that glared so loath-fully at the British youth and culture, and indeed the future of mankind, that we wouldn't touch it with a 39 and a half foot pole. That twisted, perverse Britannia of the future has now captured the minds of scholars and stoners alike and become both a cult- and academic-classic with its pessimistic, dystopian view (eschewing the original ending of the novel for something far more pessimistic, hopeless and in line with his auteurist ideals). Hyper-sexual, extremely stylized, and full of the ol' ultra-violence, Kubrick produces a nightmarish future that gazes into the very heart of the human beast, with the cultured animal Alex DeLarge raping, pillaging, relish in bloodshed and taking time to relax with some lovely Ludwig Van. His capture and torturous "rehabilitation" endeavor to rob any viewer of hope for the "good guys" winning, as one either has to force the young boy to be robbed of all his faculties to defend himself, to be beaten and destroyed by the vengeful people he's wronged (doing so being, itself, an act of spite and vengeance, ultimately creating a society turning against itself to destroy one another for all the perceived "wrongs), orlet the violent Alex go-about his cruel ways unencumbered and spare him the suffering he'd endure unable to defend himself (essentially turning a blind eye to the darkness of the world). In Kubrick's world, there's no winning, no grey area, but nor is it black and white. Indeed, it's simply choosing which side of the blackness you stand on.

Best moment:

Admittedly, applying the label "best" to this sequence has truly disturbing implications, but there's no denying it's the most memorable. Alex and his band of "droogs" bust into a man's home on the pretense of using the telephone, only to beat the man sadistically, slowly undressing and raping his wife in front of him, all while Alex belts out the classic "Singin' in the Rain" in between kicks. Forever warping a classic Hollywood tune while confirming everyone's darkest, unspoken suspicions about the true nature of man, this is a scene not forgotten by any who've seen it.

4) Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988)

4) Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988)

Undoubtedly the most obscure film on this list by far, even this author hadn't seen it or heard much of it until the votes were in for UK films and I buckled down for some research. Never would I have thought a film that appeared on the Empire 500 list below Point Break would really crack my Top Ten, but after only a few scenes, its plain to see why The Guardian dubbed it "Britain' forgotten cinematic masterpiece". Terence Davies crafts a simple, subtle story that is actually two short films: "Distant Voices" which focuses on a family in mourning over the death of their patriarch, a typical working class British father of the 50's played by the incomparable Pete Postlethwiate. "Still Lives" shows the children, now grown and married, getting together for an evening at the pub. The film jumps between points and time with ease, transitioning between moments with smooth movements that put Lone Star to shame, and endeavors to do no more than to bring post-War photographs to life. Somber moments set to music, that's the entire film, and it does it brilliantly. Music, of course, is integral to the story, from the beginning funeral dirge to the jovial songs howled both in celebration and to mask the sadder moments of life. Distant Voices, Still Lives is a brief film, a forgotten film, but it's also the best depiction of what that country was, and in some ways still is. Those pubs songs still echo faintly in every building, amidst the modern day noise, like ghosts lilting along the smoke from the cheap cigarettes, looming above as a specter of national identity. Sorry, Shane Meadows, but this is England.

Undoubtedly the most obscure film on this list by far, even this author hadn't seen it or heard much of it until the votes were in for UK films and I buckled down for some research. Never would I have thought a film that appeared on the Empire 500 list below Point Break would really crack my Top Ten, but after only a few scenes, its plain to see why The Guardian dubbed it "Britain' forgotten cinematic masterpiece". Terence Davies crafts a simple, subtle story that is actually two short films: "Distant Voices" which focuses on a family in mourning over the death of their patriarch, a typical working class British father of the 50's played by the incomparable Pete Postlethwiate. "Still Lives" shows the children, now grown and married, getting together for an evening at the pub. The film jumps between points and time with ease, transitioning between moments with smooth movements that put Lone Star to shame, and endeavors to do no more than to bring post-War photographs to life. Somber moments set to music, that's the entire film, and it does it brilliantly. Music, of course, is integral to the story, from the beginning funeral dirge to the jovial songs howled both in celebration and to mask the sadder moments of life. Distant Voices, Still Lives is a brief film, a forgotten film, but it's also the best depiction of what that country was, and in some ways still is. Those pubs songs still echo faintly in every building, amidst the modern day noise, like ghosts lilting along the smoke from the cheap cigarettes, looming above as a specter of national identity. Sorry, Shane Meadows, but this is England.

Best moment:

It's hard to pick a moment from a film that simply glides from one moment to the next with no clean scene breaks, but if forced to choose, it must be the beginning. We, the viewer, creeping through the doorway, setting the tone for the whole film's sense of spying on intimate moments, while an unseen voice sings a spiritual. Empty, emotionless faces gaze out, as though posing for a photograph no one will ever take, as their thoughts play out for us. Simple, beautiful, and powerfully devoid of heart.

It's hard to pick a moment from a film that simply glides from one moment to the next with no clean scene breaks, but if forced to choose, it must be the beginning. We, the viewer, creeping through the doorway, setting the tone for the whole film's sense of spying on intimate moments, while an unseen voice sings a spiritual. Empty, emotionless faces gaze out, as though posing for a photograph no one will ever take, as their thoughts play out for us. Simple, beautiful, and powerfully devoid of heart.

3) Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)

When talking about films from a country known chiefly for its wit, it's a bold move to declare anything "The Greatest British Comedy". If pressed to do so, it's likely any American (or even Brits with a short memory) would pick a Python film, or perhaps Edgar Wright's Cornetto trilogy, and while both groups have produced classic comedies in their time, and are respectable choices, none had the comedic streak of Ealing studios, who had a 10 year run from 1947-1957 producing classics which have been dubbed "The Ealing Comedies" and delighting audiences both in the UK and abroad, and showcasing the amazing comedic talents of the otherwise stoic Alec Guinness. Chiefly among these (and 6th on the BFI's list of Greatest Films of All Time) is Kind Hearts and Coronets, a brilliant comedy of manners and murder that could only have come from a country still so hung up on aristocracy. Louis Manzini, a poor draper in Edwardian England, grew up envious of his aristocratic relatives, the D'Ascoynes of Chalfont, for disowning his mother when she married an Italian man, and thereby keeping him far removed from ever becoming the Duke of Chalfont. In fact, the only way he could earn the title is if every D'Ascoyne in line before him (8 of whom are played by Guinness, including Lady Agatha) were to die before any of them could produce heirs. In fact, Louis spends the rest of the film ensuring just that happens. Kind Hearts and Coronets is certainly the blackest of black comedies (ok, perhaps Four Lions excepted), and holds up brilliantly despite its age (hell, a Broadway musical version just opened this year to rave reviews). One would have to be very bold to try and pick the greatest British comedy, but if one were to, they'd have to be mad not to pick this one.

Best moment:

Here Louis lays out his plan in a posh narrative, laments how difficult it is to kill people "with whom one is not on friendly terms", and we meet two of the D'Ascoynes. While perhaps not the most comical moment in the film, it sets the tone for the story ahead, and shows off the remarkable talent of Mr. Guinness.

2) Brief Encounter (1945)

2) Brief Encounter (1945)

David Lean makes his second appearance on this list in what might very well be the polar opposite of The Bridge on the River Kwai. No explosions happen here, no cast of hundreds. There's nothing sprawling or epic about this story of a sad housewife and a man at a train station. And yet, Lean pulls the film off marvelously all the same, crafting what might be cinema's greatest love story. The film is so purely English, in its subdued and proper narrative, that its hard to imagine how anyone but Lean could make it both so reserved and so passionate. Laura is in a fine but unsatisfying marriage, and one day, awaiting a train, she meets Alec, a doctor in a similar romantic plight. Dinner and trips to the cinema ensue, and soon they realize there is more between them than friendship. Attempts at an affair fail, and eventually they're forced to accept that nothing can come of it. It's the kind of story you can't sell, can't explain why it works so well, but to express how brilliantly Lean builds tension between the two in even the smallest of moments. Like real love affairs, nothing is spoken, and all is beneath the surface, as exemplified in one of the best endings in cinema, from the sadness of a goodbye unspoken to dear, sweet Fred, Laura's husband, who knows it all, though it was never spoken, and loves her all the same. It's difficult to sing the praises of Brief Encounter as this kind of delicate, subtle filmmaking rarely happens anymore (the closest comparison would be Matthew Weiner's television program Mad Men), particularly a romance unconsummated like this one. Yet the film works so brilliantly, with such emotional resonance, that it simply must be seen. Though short, much like the affair between Alec and Laura, it remains unforgettable, staying forever in our hearts as something truly honest and human.

Best moment:

What sets Brief Encounter apart, beyond its story, is its mastery of the visual craft. Every shot, no matter how simple, is designed to create tension, and tell the story that's not allowed to rise above the surface. No better example of this exists than Laura going to the apartment Alec has arranged for them. From her moments on the train where she just almost blends in, nearly being another face i the crowd, to her flee through the tunnel beautifully capturing her descent into full infidelity, to the way the camera creeps behind a window, making us both a voyeur observing the salacious affair and Laura herself, feeling that shame as though eyes were watching her. Lean's visually mastery has only once been on better display than this film, which on its own could be a master class on shot choices.

1) Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Lieutenant T.E. Lawrence: Soldier? Warlord? Mad man? Who was the famed Lawrence of Arabia? The film starts by asking the question, but never answers.

When it was decided British cinema would be the topic of our next list, I spent the next two weeks watching as many esteemed British films as I could, trying to catch everything I'd missed, ranking as I went. From the day I was born to the writing of this very sentence, I have now seen over 150 films that are solely British productions in accordance with the restrictions we'd created for this blog. But a small part of me knew, from the minute the votes were tallied, that Lawrence of Arabia would take #1. It was always Lawrence, and would always be Lawrence. David Lean's titanic masterpiece, which won 7 Oscars including Best Picture, ranks #5 on the AFI list of the Greatest films of all time, and #3 on the BFI, has influenced everyone from Sergio Leone (who would use the oasis in For A Few Dollars More) and George Lucas (whose Star Wars films lifted heavily from Lawrence, including locations, cast members, and musical motifs) to Ridley Scott (who used scenes from the film in Prometheus) and Steven Spielberg, who credits Lawrence as the reason he became a director.

From its sweeping score to its stunning visuals and stellar cast, Lawrence of Arabia isn't just cinema's finest epic, but easily one of the greatest films of all time, for it both exemplifies the genre of "epic" while avoiding its pitfalls, namely that performances suffer since such grandiose storytelling never finds time for personal moments, or if it does, it kills the pace of the film. Lean, however, achieves this by allowing his actor (the tremendous Peter O'Toole in the role of a lifetime) to have internal conflicts in these big moments. No need for monologues or diatribes after the fact to try and "add emotional context" to big action scenes. Rather, he lets an eye twitch, or a scowl, or a smile, or perhaps all three within a single moment, tell the struggle within the titular Lawrence. The man we follow in this film is both extraordinary and yet undeniably human. He struggles, he suffers, he teeters on the brink of madness.

Lawrence of Arabia does what no other historical epic ever has, in that it finds intimacy amongst the massive set pieces. We see the tortured look upon the face of T.E. as he shoots his friend, or debates whether to charge into a bloody battle that matters not to the grand plans of the elusive Damascus. And Damascus is more than just a destination to Lawrence. It is a promised land, but built of a false promise. After a near 3 hour journey, both across the desert and into the darkest depths of the human beast within him, he reaches the fabled Damascus and conquers it, only to find the Arab council he'd hoped for to be a failure, an assemblage of bickering tribesman unable to attain the state of harmony Lawrence sees was foolish to hope for. In the end, perhaps Lawrence was an idealist. Perhaps he was all of our idealism.

Then again, perhaps he was just a man. He was every man; peaching for peace but craving bloody retribution, too hopeful for his own good, and with a very funny sense of fun. It's not just O'Toole's performance that conveys this idea, but indeed the entire film. David Lean's masterful filmmaking uses every shot of desert, every cue of orchestral melody, even the near dream-like colour of the hot sun rising over the sand, to craft a complex and beautiful portrait of a complex but beautiful man. There are many ways to Describe Lawrence the man, but only one suits the film, a label applied often to other films but rarely deservedly so: Perfect.

When it was decided British cinema would be the topic of our next list, I spent the next two weeks watching as many esteemed British films as I could, trying to catch everything I'd missed, ranking as I went. From the day I was born to the writing of this very sentence, I have now seen over 150 films that are solely British productions in accordance with the restrictions we'd created for this blog. But a small part of me knew, from the minute the votes were tallied, that Lawrence of Arabia would take #1. It was always Lawrence, and would always be Lawrence. David Lean's titanic masterpiece, which won 7 Oscars including Best Picture, ranks #5 on the AFI list of the Greatest films of all time, and #3 on the BFI, has influenced everyone from Sergio Leone (who would use the oasis in For A Few Dollars More) and George Lucas (whose Star Wars films lifted heavily from Lawrence, including locations, cast members, and musical motifs) to Ridley Scott (who used scenes from the film in Prometheus) and Steven Spielberg, who credits Lawrence as the reason he became a director.

From its sweeping score to its stunning visuals and stellar cast, Lawrence of Arabia isn't just cinema's finest epic, but easily one of the greatest films of all time, for it both exemplifies the genre of "epic" while avoiding its pitfalls, namely that performances suffer since such grandiose storytelling never finds time for personal moments, or if it does, it kills the pace of the film. Lean, however, achieves this by allowing his actor (the tremendous Peter O'Toole in the role of a lifetime) to have internal conflicts in these big moments. No need for monologues or diatribes after the fact to try and "add emotional context" to big action scenes. Rather, he lets an eye twitch, or a scowl, or a smile, or perhaps all three within a single moment, tell the struggle within the titular Lawrence. The man we follow in this film is both extraordinary and yet undeniably human. He struggles, he suffers, he teeters on the brink of madness.

Lawrence of Arabia does what no other historical epic ever has, in that it finds intimacy amongst the massive set pieces. We see the tortured look upon the face of T.E. as he shoots his friend, or debates whether to charge into a bloody battle that matters not to the grand plans of the elusive Damascus. And Damascus is more than just a destination to Lawrence. It is a promised land, but built of a false promise. After a near 3 hour journey, both across the desert and into the darkest depths of the human beast within him, he reaches the fabled Damascus and conquers it, only to find the Arab council he'd hoped for to be a failure, an assemblage of bickering tribesman unable to attain the state of harmony Lawrence sees was foolish to hope for. In the end, perhaps Lawrence was an idealist. Perhaps he was all of our idealism.

Then again, perhaps he was just a man. He was every man; peaching for peace but craving bloody retribution, too hopeful for his own good, and with a very funny sense of fun. It's not just O'Toole's performance that conveys this idea, but indeed the entire film. David Lean's masterful filmmaking uses every shot of desert, every cue of orchestral melody, even the near dream-like colour of the hot sun rising over the sand, to craft a complex and beautiful portrait of a complex but beautiful man. There are many ways to Describe Lawrence the man, but only one suits the film, a label applied often to other films but rarely deservedly so: Perfect.

Best moment:

As this is one of my favorite films (as well as one of the all-time beloved by film scholars), picking one moment would be impossible, so I've opted for two. The first is the most technically brilliant, and inarguably the most copied scene of this or almost any film, the famous match cut. After describing how "fun" he believes his time in the desert will be, Claude Raines tells O'Toole he has a "very funny sense of fun", already hinting at how off-beat the man we'll spend the next 4 hours with is. Then Lawrence, with angelic smile on his face, blows out a burning match as we're greeted by our first real look at this sweeping land of sand Lawrence tried to tame. The sun rises over the horizon as Maurice Jarre's brilliant theme swells, kicking off the epic journey.

However, the scene this writer personally loves, the one that moves him most deeply, is undoubtedly when Lawrence and his now large army spy some retreating Turks who had just slaughtered the village of Tafas. When one man, who came from that village, demands Lawrence charge on them, taking no prisoners, Lawrence hesitates. The man then charges alone at the Turks and was shot. In this moment, we don't just see a shift in Lawrence's attitude and attribute it to him "snapping" as most films ask us to do, filling in blanks. Instead, Lean treats us to the full moment of Lawrence, face wrenching, eye twitching, gazing upon the fallen body. We see the massive emotional journey of just a split second as Lawrence finally relents to his inner hunger for violence, shouting "No prisoners" before joyously slaughtering the Turks. It's the kind of a moment that's so rawly human, and yet so massively cinematic, that none have ever been able to match it.

However, the scene this writer personally loves, the one that moves him most deeply, is undoubtedly when Lawrence and his now large army spy some retreating Turks who had just slaughtered the village of Tafas. When one man, who came from that village, demands Lawrence charge on them, taking no prisoners, Lawrence hesitates. The man then charges alone at the Turks and was shot. In this moment, we don't just see a shift in Lawrence's attitude and attribute it to him "snapping" as most films ask us to do, filling in blanks. Instead, Lean treats us to the full moment of Lawrence, face wrenching, eye twitching, gazing upon the fallen body. We see the massive emotional journey of just a split second as Lawrence finally relents to his inner hunger for violence, shouting "No prisoners" before joyously slaughtering the Turks. It's the kind of a moment that's so rawly human, and yet so massively cinematic, that none have ever been able to match it.

Best Director in British Cinema

David Lean

Did I even need to say it? Three of his films made the Top Ten (far more than any other director). Yes, Hitchcock was also a Brit, but his best work wasn't until he came stateside (and personally I prefer Lean's work anyway, but let's try and keep objective here). Lean's work spans genres, decades, techniques and run times. From his first (In Which We Serve) to his last (Passage to India), it was a stream of classics. He's known for his epics, like Lawrence, Kwai and Doctor Zhivago, but he works just as brilliantly in kitchen-sink dramas like Brief Encounter and The Passionate Friends, to say nothing of his definitive takes on the works of Dickens (who was to Brit- literature what I'd argue what Lean was to cinema). David Lean made films that were internationally loved, universally understood, and yet still quintessentially British, forever earning his place as the finest filmmaker in the nation's history.

Honorable Mentions

Drama:

- The David Lean adaptations of Dickens, Oliver Twist (again featuring Alec Guiness) and Great Expectations.

- Laurence Olivier's trilogy of Shakespeare adaptations: Richard III, Hamlet, the the definitive version of Henry V.

- The other classic Bond films; particularly the rudimentary (Dr. No, From Russia With Love), the gritty reboot (Casino Royale), and the stellar return to form (Skyfall).

- The Man Who Fell To Earth, Brazil and this year's Under The Skin; all of which to sci-fi the only way the British know how, as bleak reflections of modern life and the inevitable failure of man.

- The moving, beautiful, fanciful The Red Shoes.

- Dirty Pretty Things, which forces the viewer to stare into the abyss of an immigrant's life in the land of hope and glory, guided at-the-time unknowns Audrey Tautou (Amelie, The Da Vinci Code) and Chiwetel Ejiofor (Serenity, 12 Years A Slave).

- This Sporting Life, Britain's answer to A Streetcar Named Desire, with all the attendant working class ambience, tight t-shirt brooding and mid-century misery.

Comedy:

- Naturally, one can't talk about British comedy without discussing the Monty Python films; in particular, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, The Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life, which many would call the "holy trinity" of Python films (and if you find the use of the term "holy trinity" blasphemous, you might just wanna skip Life of Brian).

- The other magnificent Ealing comedies, as mentioned above, particularly Passport to Pimlico, Whiskey Galore!, The Man in the White Suit, The Lavender Hill Mob and The Ladykillers.

- Edgar Wright's brilliantly funny genre parodies dubbed "The Cornetto Trilogy"; the zombie-hacking Shaun of the Dead, the off-the-fucking-chain action of Hot Fuzz, and the apocalyptic pub crawl The World's End (though this writer would argue that the original Wright/Simon Pegg/Nick Frost effort, the TV series Spaced is better than all three, but we're here to talk film).

- What some consider the origin of the music video, and others tout as a brilliant time-capsule of Beatlemania, A Hard Day's Night often doesn't get the credit for what it truly is, which is a brilliantly clever and funny movie, in line with the best Ealing comedies. While the other cinematic endeavors of The Beatles are a pain for any non-fans, this first film works just almost as well were its leads different men and its music bland. The story just works.

- For as uptight as we paint the Brits to be here in the US of A, they can be about as un-PC as it gets (check The Inbetweeners or Little Britain if you don't believe me). That's why you've got to go across the pond for a flick like Four Lions, a screwball comedy about Islamic terrorists.

- A movie both of-its-time and yet still timeless at its core, the Amero-Anglo romance tale Four Weddings and a Funeral gives us Hugh Grant at his best, as well as John Hannah (the other guy from the Mummy series) delivering "Funeral Blues" so beautifully as to spark a mini-revival of W.H. Auden's work.

- Alfie: Skip the Jude Law reboot and check out the brilliant original, starring Michael Caine in one of his finest performances.

- The Full Monty, as there's something about a group of sad-sack unemployed men, none of which terribly attractive, so desperate for money and a sense of purpose that they close their eyes and think of England whilst stripping that's just so...well, English.

- What has found itself being the new quintessential love story/Christmas film, even though its bevy of British stars are virtual unknowns here, Love Actually is as sweet and endearing now as it was 10 years ago, with a sense of humble optimism the American attempts (Valentine's Day, New Year's Eve) were too bombastic to match.

- The rule was no UK/US co-productions, which means I can't talk about any kind of, let's say, cult classic by masterful writer Martin McDonagh, like, for example, one which takes place in Bruges. However, Seven Psychopaths can be mentioned. So check that one out. But if you mistakenly grab a different film by Martin McDonagh starring Colin Farrell instead, you might have an even better time. Just saying.

- Few cartoon characters have better captured a culture than Nick Park's nationally and internationally beloved Wallace and Gromit. Previously stuck only in shorts, the duo finally got their chance to stretch their legs in a feature length endeavor with the delightful Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Wererabbit.

- If This Sporting Life is Britain's Streetcar, than Billy Liar is it's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, following (and condemning) a young daydreamer as he chases tail and wastes his days.

- Universal Pictures' 1939 adaptation of Gilbert & Sullivan's The Mikado was not only the first cinematic take on one of their works, it remains the best.

Historical:

- The Oscar-Nominated and then sadly forgotten An Education, a brilliant Sixties-set coming of age story that brought us Carrie Mulligan.

- 24 Hour Party People, the true story of Tony Wilson, plays like a Forrest Gump of the Manchester music scene, from the fall of Joy Division's Ian Curtis to the rise of ecstasy (with a fresh off of Fellowship Andy Circus popping 'round as Martin Hannett).

- A woefully grave look at the rise of the skinhead culture in the UK, This Is England is a haunting look at the dark side of "national pride", even if it does lift its ending from The 400 Blows.

- Tom Hardy gives a career best performance (the likes of which pretentious dreamscapes and moronic masks have since hindered) in Bronson, the tale of an English pseudo-celebrity who made art of his violence.

- England has produced countless films that look back nostalgically about growing up in the rubble of World War 2, some more insufferable than others. But I would be remiss if I didn't include one, John Boorman's Best Picture nominated Hope and Glory, which stands out above the rest.

- Is it dated? Yes, but Zulu is still the best depiction of a crucial turning point in Britain's colonialist ways (unless you count the "tiger attack" scene in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life).

- Elizabethan history can be kind of a drag to dramatize, and most attempts rely on anachronisms or pretty clothes to hook the viewer. Shekhar Kapur, however, used his 1998 biopic of England's greatest ruler (Elizabeth) to reinvigorate interest in her story with one name: Cate Blanchett. Visually stunning and brilliantly written, the film's strongest asset is still undeniably the captivating and live wire performance of the two-time Oscar winner.

- There's been backlash since it won Best Picture over a more deserving film (older voters might have found Jesse Eisenberg's Zuckerberg to be as much of a creep as the trailer suggested), but there is a power to The King's Speech that is undeniable. Using a deeply personal and intimate struggle to reflect a nation's unrest in the dawn of the second World War, Tom Hooper's simplistic, up close style of shooting works well here (unlike a certain musical) to capture a remarkable performance by Colin Firth as King George, with the film reaching it's climax with the delivery of his famous speech, which may now forever by intertwined with Beethoven's 7th Symphony.

- Long before Universal Pictures made their above-mentioned Mikado, Gilbert & Sullivan had to write it. And the story of how they did, it turns out, is even more interesting than what they wrote. Beloved English auteur Mike Leigh uses the biographical tale of Topsy Turvy to explore Victorian life in a manner that doesn't feel stale or dated, and brings together a stellar cast (all of whom sang all of the music themselves) lead by Jim Broadbent and Allan Corduner, as well as featuring, in a small role, Shirley Henderson (who pretty much steals my heart in whatever she appears in).

Crime:

- The BFI's pick for the greatest British film ever made (because Orson Welles can't just appear in one perfect film), Carol Reed's The Third Man is a crime thriller unlike anything we'd ever get stateside. Its subdued without being dull, entrancing in its mystery with not one single car chase (perish the thought). Harry Lime remains one of the most engaging villains in cinema, and The Third Man stands to this day as an example of how to do it right.

- While nothing Hitchcock did before traveling stateside ever came close to The 39 Steps, he left another indelible mark on Brit-cinema with the thrilling train-bound mystery The Lady Vanishes, which takes many elements used in The 39 Steps and tosses in more than a dash of Agatha Christie to enthrall viewers with its titular mystery.

- One cannot talk about British crime films without discussing the classic: Get Carter. With Michael Caine in peak form and full of that 70's swagger, the film smolders in the screen like a burning cigarette in the lips of the entrancing Britt Eckland.

- Modern British crime films, while owing a great deal of debt to the 70's boom, are truly, undeniably just trying to play catch up with the new king of UK action, Guy Ritchie. His pair of Statham starring masterworks, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch reminded the world of what could be done with a few guns, some cool accents and some wickedly funny dialogue.

- God damn, the Mini-Cooper never looked as cool as it did in Peter Collinson's robbery romp, The Italian Job, with Michael Caine taking the rains as the brilliant Charlie Crocker, joining a gang of robbers lead by the great Noel Coward, to prove the English could keep up with the Americans in terms of vehicular excitement on screen. As Caine would later tell his on-screen son Austin Powers, "It's not the size of the car, it's what you do with it".

- The new film-school favorite Christopher Nolan first demonstrated his trademark flair for mind-bending mystery in his independent feature debut, Following, which puts his Hitchcock homaging on full display, while showing an eerie bit of foreshadowing with a Bat-symbol cropping up in a cameo.

Horror:

- One of the most haunting horror films ever made, The Wicker Man burns on the screen with a mad intensity in no small part due to Hammer Horror darling Christopher Lee as the creeping specter of paganism (a creepy concept to the still conservatively religious England).

- The Hammer Horror films, particularly Christopher Lee's Dracula, which function as Britain's answer to the bellowed Universal Monster movies, but with more of a swinging sixties kind of vibe.

- 28 Days Later, for near single-handedly reviving the zombie genre with it's post-9/11 look at humanity in dire circumstances.

- Paddy Considine (best known stateside from The Bourne Ultimatum) writes and stars in on of the finest revenge thrillers of all time, Dead Man's Shoes. To say more would be to spoil it, as is the case with the next entry, but know you'll never look at a gas mask the same way again.

- Ben Wheatley's Kill List. Read nothing, just watch and enjoy the ride.

From the TV to the Screen:

- Armando Iannucci is a master of the comic word, and his adaptation of the political comedy series The Think of It (starring a rather foul-mouthed Doctor named Peter Capaldi), entitled In The Loop skewerd Anglo-American politics and proved James Gandolfini can be funny as hell.

- Another Iannucci creation is Steve Coogan's conceded and clueless disc-jockey/talk-show host/again disc-jockey Alan Partridge. After radio and television shows, Coogan took to the screen in Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa, as his ABBA-loving idiot found himself the only man to solve a hostage crisis at his employer, Radio Norwich.

- The cult coming-of-age series The Inbetweeners is a show that could only exist in the UK (we tried here on MTV, but our language restrictions forbid our characters from making poetry out of the perverse quite like James Buckley can). The Inbetweeners Movie serves as a wrap up for the series (which unceremoniously ended after Series Three because British television has to take away everything you love before its time), sending the boys to Crete after leaving Rudge Park Comprehensive. It was meant to be the last chapter in the saga of Simon, Will, Jay and Neil, but the film proved so popular, they're making a sequel, shipping the fellows off to Australia. The first two series and the movie are on Netflix, so take the opportunity to catch up, if want to taste of how similar (and in some ways, how different) high school is for those in the land of tea and crumpets.

So that's it for UK films. Don't forget to check out Tom and Josh's blogs to get a second and third opinion on the cinema of the Brits. Thanks to everyone who voted. Please, feel free to share your comments below, and I encourage any who haven't to see the above films. It's a way to explore another culture without having to deal with subtitles, America. I mean, at this point it's practically cheating.

Want to pick what we write up next? Cast your vote below: